Sara Blakely learned early that failure was not something to hide. It was something to lean on. That belief shaped how she built Spanx, shared her story, and became the youngest self-made female billionaire.

In this issue, I break down Sara’s founder journey and why reframing failure became one of her greatest advantages. You’ll also find:

3 storytelling lessons on using vulnerability to create connection

Fun facts on just how big the Spanx movement has become

A video where Sara shares the hardest moments, the rejection, and how she kept going through years of no’s

Enjoy learning how Sara shaped society, literally and figuratively…LG

Founder Story: Sarah Blakely, SPANX

Sara Blakely graduated from college with a degree in legal communications. Her plan was straightforward: become a lawyer, following in her father's footsteps. But she struggled with the LSAT and failed to pass it despite multiple attempts.

Luckily, thanks to a childhood lesson from her father, that didn't stop her. At the dinner table growing up, Sara's father would always ask her and her brother:

"What did you fail at this week?"

If they had nothing to report, their dad would be disappointed. Failure wasn't something to avoid. It was proof you were trying. The real failure was playing it safe.

So when law school door closed, Sara decided to try something fun instead. She applied to work at Disney World with one goal: play Goofy.

She auditioned but missed the height requirement by one inch. They offered her a chipmunk role instead, but Disney made you wait three months before trying out for a different character. She sold tickets in the meantime. That wasn't the dream, so she quit and took a job at Danka selling fax machines door-to-door.

THE GRIND

For years, Sara sold fax machines across Florida, cold calling every account. That meant constant rejection. People ripped up her business card. She was escorted out of offices. Doors closed. Voicemails went unanswered.

It became an unexpected training ground. She learned how to sell without authority, brand, or leverage. She learned how to hear no without absorbing it.

During this period, driving between sales calls, she hit a personal reckoning. She felt she was living the wrong life.

Sara pulled her car over, grabbed a pen, and wrote down what she was good at. Sales made the list. She also wrote a sentence that read like a mission statement:

I want to invent something that I can sell to millions of people that will make them feel good.

At the time, she had no product, no plan, and no industry connections. But the intention was set.

THE AHA MOMENT

Selling fax machines in Florida in the summer was brutal. Because of the heat, Sara wanted to wear open-toed shoes. At the same time, she wanted the smoothing effect of pantyhose so her butt looked good in white pants.

The problem was obvious. Pantyhose looked terrible with open-toed shoes.

One night, getting ready for a party, Sara grabbed a pair of scissors and cut the feet off her pantyhose. She got the control-top effect without anything showing at her feet.

This was it. That was the unique product idea Sara had been waiting for. If she needed this, other women did too.

THE YEAR OF SILENCE

Sara didn't tell anyone about the idea for an entire year while she kept selling fax machines. She wanted space to think without noise, without people telling her why it wouldn't work.

She visited department stores and asked sales associates simple questions. What do women wear under white pants? The answers confirmed the gap. Existing shapewear was bulky, uncomfortable, or poorly designed.

Living close to work, Sara started driving aimlessly before and after her shifts. Friends called it her "fake commute." It became her time to think through problems and refine the idea.

$5,000 AND A LIBRARY CARD

Sara committed $5,000 of her savings to the idea. It was nearly everything she had.

She had no fashion background. No manufacturing experience. No business degree. So she taught herself.

When she called patent attorneys, they laughed or quoted fees she could not afford. Instead, she went to the library. She studied patent filings, bought patent books from Barnes & Noble, and learned how to file on her own.

She wrote the patent herself, paying a lawyer a small fee only to review the technical details.

1st SPANX Store

TWO YEARS OF NO

Finding a manufacturer nearly killed the company before it started. Most hosiery manufacturing was in North Carolina. Sara traveled there repeatedly, walking into factories and pitching her idea.

Every conversation ended the same way. No.

Manufacturers tested products on plastic molds, not real women. The industry was male-dominated, and these decision-makers couldn't relate to the problem Sara was solving.

This rejection cycle lasted for months. But Sara treated rejection as expected friction, not as feedback on her worth. Each no was just part of the process, leaning on her father's lessons.

This is where vulnerability stops being a concept and becomes a practice. As we explored in the previous issue, choosing not to armor up after rejection is what allows trust, learning, and momentum to continue. Sara did not hide the no’s. She absorbed them and kept showing up.

Luckily, one of the men she pitched who told her ‘no’ had two daughters. That night, after he rejected Sara, he went home and told them the idea. They thought their dad he was crazy for turning her down and convinced him it was a great idea.

The next day, the manufacturer called Sara, told her what happened, and said he was in.

Elated, Sara moved on to the next challenge: packaging.

Sara Blakely with one of her famous mugs she posts regularly about on social media

ILLUSTRATIVE PACKAGING & LUCKY BACKPACKS

Once manufacturing began, Sara refused to follow industry standards. Instead of testing on mannequins, she tested on real women. Friends. Family. Different body types.

They wore the product in daily life and gave blunt feedback. Uncomfortable waistbands were adjusted. Fabric that rolled was redesigned.

Sara looked at the hosiery aisle and saw the same thing everywhere. Beige and gray boxes. Airbrushed, half-naked models. Packaging that felt dated and impersonal.

She wanted the opposite.

So she chose bright colors and cartoon illustrations of women. Not to be cute, but to be clear. This product was made for real women, not mannequins.

In a category built on blending in, Spanx stood out before anyone even picked it up.

Bright colors and illustrations were the hallmark of Spanx early days

Once she had the packaging, prototype, and name, she called the Neiman Marcus store in Atlanta to pitch them. They told her she had to call the buying office in Dallas not knowing there was such a thing as a ‘buying office’.

Sara called Dallas, introduced herself, and talked about her product that was going to change the way women wore clothes.

The buyer suggested she mail in a sample, but Sara pushed back and asked for ten minutes in person, knowing she'd sell Spanx better face-to-face than in a box. The woman agreed.

Sara bought a ticket to Dallas and boarded the plane with her lucky red backpack, which she'd had since college. Her friends pleaded with her to buy a Prada bag and return it when she got back. But to Sara, the backpack was special.

It was the one constant she lugged through long days selling fax machines in the Florida heat, stuffed with rejection, ideas, and early Spanx sketches. The backpack had been there for every small, invisible bet she'd made on herself. Leaving it behind felt like leaving herself behind.

THE BATHROOM FASHION SHOW

She arrived at the Dallas Neiman Marcus offices with her footless Spanx, a color copy of the packaging she'd created on her friend's computer, and her lucky backpack.

About five minutes into her presentation, she realized the buyer still didn't quite get it. So Sara pivoted and said, "Come with me to the ladies' room."

In the bathroom, she changed into white pants and did an on-the-spot before-and-after demo, first without Spanx and then wearing Sara's creation.

That two-minute visual convinced the buyer on the spot. The difference was obvious. The buyer placed an order for seven stores.

NIGHTS AND WEEKENDS

Sara was still working full-time selling fax machines when the first orders shipped. At night, she packed Spanx orders by hand using padded envelopes from office supply stores. Her apartment became a fulfillment center.

By the end of its first year, Spanx generated $4 million in revenue. No marketing team. No employees. No ad spend. No outside capital.

Growth came from three places: retail placement near fitting rooms, in-store demonstrations where Sara trained associates herself, and word of mouth between women. Sara waited to quit her day job until the business proved it could stand on its own.

OPRAH CHANGES EVERYTHING

The single most important acceleration moment for Spanx came in November 2000.

Sara had identified Oprah Winfrey early as the ideal person to get the product in front of. Oprah had openly discussed weight fluctuation and body confidence on her show for years, making her a natural fit.

Acting on that belief, Sara assembled a gift basket specifically for Oprah and her team, filling it with Spanx products along with a personal note explaining what the product did and why women loved it.

Someone on Oprah's staff who often dressed Oprah pulled Spanx from the basket, had Oprah try them on, and discovered they worked so well that Oprah started wearing them daily.

The Oprah team then called Sara and told her that Spanx had been chosen as Oprah's "favorite product of the year," to be featured on the Oprah Winfrey Show's "Favorite Things."

Orders flooded in. Inventory vanished. Shortly after the episode aired, Sara quit her fax machine sales job. Spanx crossed $10 million in revenue in its second year.

But the Oprah endorsement did more than drive sales. It normalized shapewear as a public conversation. Women could now talk openly about undergarments without shame or secrecy. That cultural permission was as valuable as the revenue itself.

GROWTH WITHOUT ADS

For the next decade, Spanx spent zero dollars on traditional advertising. It started as a constraint and evolved into strategy. Sara believed women trusted other women more than ads. So the company engineered growth around human behavior.

Packaging stood out with bright red, cartoon illustrations, and conversational copy. Retail placement was intentional, near shoes and fitting rooms. Sara personally trained retail associates. She clipped bylines from magazines and cold-called journalists directly. Celebrity gifting replaced paid endorsements.

The story traveled faster than ads ever could.

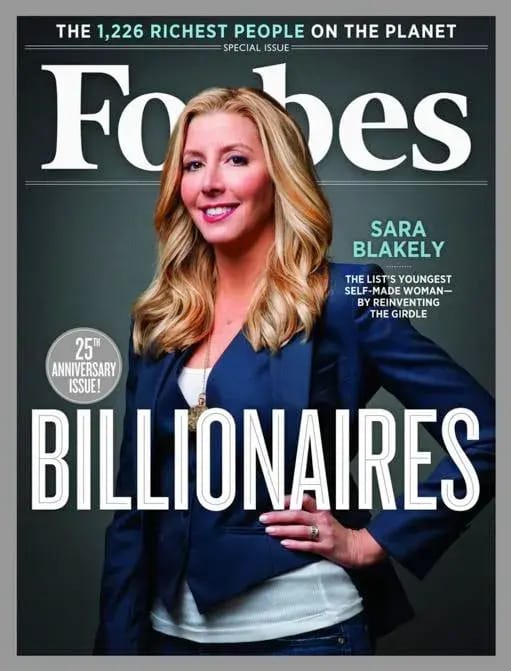

Sara became the youngest self-made female billionaire in the world at age 41.

In 2021, Blackstone acquired a majority stake valuing the company at $1.2 billion, the first outside investment in its history.

Today, Spanx generates $400 million in revenue, sells in more than 50 countries, and is valued at over $2 billion.

Storytelling Lessons:

Sara scaled Spanx exponentially because she made her story part of the product. By sharing her failures openly, reframing rejection, and using vivid moments instead of abstractions, she built trust and belief at scale. These 3 lessons show how she used storytelling as a growth lever and how founders can apply the same moves to their own story.

Make Vulnerability the Hook

Sara leads with what went wrong. Failing the LSAT. Being too short to play Goofy. Selling fax machines door to door and getting rejected daily. She does not clean these moments up or rush past them. She uses them to lower defenses and build trust fast. Vulnerability makes her relatable before she ever talks about success.

ACTION: Pick one failure that shaped how you think today. Share it early in your story. Do not justify it or soften it. Let the audience see you before you try to impress them.Turn Failure Into Forward Motion

Failure is not a detour in Sara’s story. It is the path. Her father taught her that failure meant effort, not defeat. That belief shows up everywhere. Instead of hiding those moments, she uses them to show momentum. Each setback points directly to the next decision.

ACTION: Line up your failures in order. Show how each one forced a choice or shift. You don’t have to explain the lesson. Let the progression do the work.Show It, Do Not Explain It

Sara’s story sticks because it is visual. Cutting pantyhose with scissors. Carrying a red backpack into Neiman Marcus. Demonstrating Spanx in a bathroom instead of a boardroom. These are scenes people can picture. She shows value through action, which makes the story easy to remember and repeat.

ACTION: Replace one abstract explanation in your story with a specific moment. Name the place, the object, and the action. If someone can picture it clearly, it will travel further.

Fun Fact: The Cut That Built a Category

The Spanx name quickly became shorthand for modern shapewear, and at its peak the brand has held a dominant share of the U.S. shapewear market, with some industry reports estimating Spanx at around 20% or more of U.S. shapewear sales despite never taking venture capital, private equity, or institutional funding.

When she later sold a majority stake to Blackstone at a roughly $1.2 billion valuation, to mark the moment, Sara Blakely gave each of her 750 employees $10,000 in cash and two first-class plane tickets.

Video to Watch: Scissors, Setbacks, & Mindset

In this visit to the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Sara shows up exactly as she is. She opens with an awkward backstage moment, then walks students through the hardest parts of getting Spanx off the ground, including the rejection, doubt, and long stretches of no momentum. She breaks down her origin story, how she learned to reframe failure, and why starting small while thinking big kept her moving forward when quitting would have been easier. Watch here:

Sara Blakely, Founder and CEO, Spanx, Stanford School of Business

Need help with your story? I got you.

Send an email to [email protected] and someone from my team will circle back with you.